Lenin

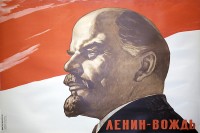

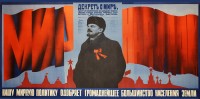

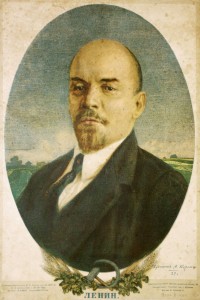

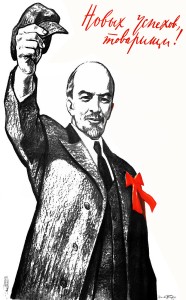

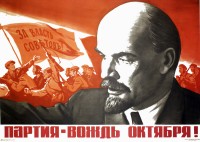

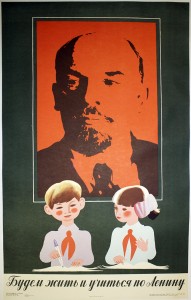

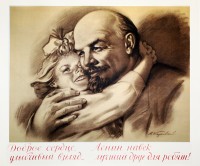

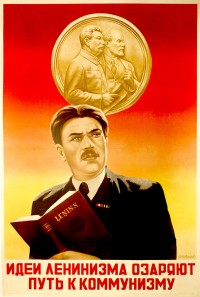

When Vladimir Lenin died in 1924, the Soviet Union mourned. Josef Stalin, in his new role as Secretary of the Party, encouraged Lenin's cult-like veneration. Embalmed and displayed in Moscow's Red Square---where his body still remains---Lenin featured prominently in official art and propaganda until 1991. Born in 1870, Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov became radicalized when his brother was executed in 1887 for plotting to assassinate the Tsar. Taking the pseudonym Lenin after publishing his first book in 1900, he became a central but divisive figure in the nascent Russian Social-Democratic Workers Party. [Text continues at bottom of page]

In 1902, Lenin's political pamphlet , What Is To Be Done? The Burning Questions of Our Movement, was published. In it, he argued a workers' party invited only police infiltration and arrest. He reasoned that radicals should form a professional vanguard to lead the masses when revolution became possible. This position split the party in 1903, when Lenin declared his followers "the majority," or Bolsheviks. The advocates for a workers' party became "the minority," or Mensheviks. Lenin remained in European exile almost continuously from 1900 to 1917, and in contrast to his comrades, who were harried by police and often exiled to Siberia, Lenin lived a conventional life outside Russia that starkly contrasted with his unbending political radicalism.

World War I changed everything. In August 1914, each of Europe's socialist parties violated their internationalist principles by supporting their state's entry into World War I. Vehemently opposed to the war; Lenin was stranded in neutral Switzerland, separated from the Russian Empire by German and Austrian territory. Receiving word of the February Revolution in March 1917, Lenin grew so desperate to reach Petrograd he accepted aid from German authorities who, knowing of his antiwar convictions, hoped to induce Russia to quit fighting. They arranged Lenin's passage to Russia, a compromise that dogged Lenin with unfounded charges that he was a German agent. Arriving in Petrograd, Lenin voiced radical positions unpopular even among his own followers. Denouncing Russia's Provisional Government consisting of liberals and moderates, he advocated for handing power to popular councils---soviets---representing workers and soldiers. Lenin's slogans offering "Peace, Land, Bread" to a war-weary population attracted a mass following. Bolshevik party membership swelled from thousands to hundreds of thousands. Although his presence---and zealotry---proved decisive in the course of events, he had to overcome skepticism within his own inner circle up to the very moment of the Bolshevik Revolution of November 7 (October 25 o.s.).

Established during the October Revolution, the Sovnarkom (Council of People's Commissars) was headed by Lenin, whose ideas proved crucial.

Having pledged to end the war and lacking an army to fight it, the Bolsheviks sought negotiations with Germany. In March 1918, Lenin demanded that Sovnarkom accept the harsh German terms for peace because he believed that imminent revolution in Germany would make Russia's concessions moot. Lenin responded to setbacks---including an assassination attempt---by sanctioning terror against those considered hostile to the revolutionary state.

By the end of 1921, Soviet Russia had largely secured itself against its enemies but it remained in crisis. After the Russian Civil War, famine loomed, peasant rebellion raged, and even Lenin's supporters denounced the authoritarianism of the Communist Party. In response, Lenin combined repression with economic concessions via the New Economic Policy (NEP) that briefly decentralized the state-controlled marketplace. While Lenin considered the NEP a pause on the march toward communism, it succeeded in bringing back Russia's ailing economy.

In May 1922, Lenin suffered an incapacitating stroke. By December, he recovered only enough to dictate his so-called testament, an assessment of his fellow comrades in the Soviet leadership. His testament intended to encourage cooperation among the leaders rather than exacerbate a struggle for individual power. Provoked by Josef Stalin's response, Lenin dictated an addendum suggesting the removal of Stalin as head of the Communist Party, a fate Stalin dodged by tactical maneuvering, and by calling on the loyalty of beneficiaries under his patronage. This put Stalin on the path to political dominance even before Lenin's death in January 1924.

Suggested Reading

Seventeen Moments of Soviet History, "The Death of Lenin," http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1924-2/death-of-lenin/

Service, Robert. Lenin: A Biography (Macmillan, 2000).

Tumarkin, Nina. Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Harvard University Press, 1983/1997).

Volkogonov, Dmitri. Lenin: A New Biography (Free Press, 1994).

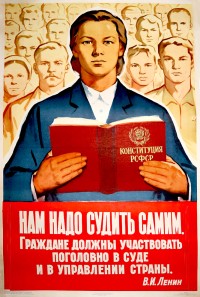

![PP 172: KPSS [Communist Party of the Soviet Union]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-172/pp172-179x300.jpg)

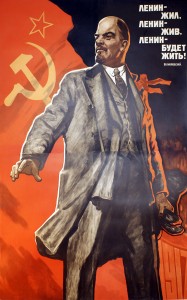

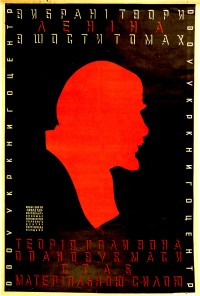

![PP 976: Be as was the Great Lenin.

Electors; the people should require from their deputies that they do their tasks to the utmost, that in their work they do not lower themselves to the level of the political peon, that they remain at their posts as political activists of the Leninist type.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-976/pp976-198x300.jpg)