Education & Literacy

Confronting civil war in 1919, Russia's Bolshevik-dominated government faced many troubles: economic depression, agricultural breakdown, exodus from cities, enemies on every front and, weakening military capabilities. Amid the chaos, the Bolsheviks still devoted attention to mass literacy. The Council of People’s Commissars issued a January 29, 1919 decree, “On liquidation of illiteracy among the population.” The resulting campaign offered primary education and adult reading programs as defined under the acronym, Likbez (Likvidatsiia bezgrammotnosti) or, “Liquidation of Illiteracy.” [Text continues at bottom of page]

Historically, the number of children attending peasant schools rose four-fold in the 30 years after 1885. Church schools also provided access to reading, as did the army for those men conscripted after a series of military reforms in the 1870s. The urban working class, where men predominated, tended to be more literate, as shown by a 1918 survey finding a rate of nearly 64 percent. However, the patriarchal nature of society likely ensured that literacy rates for men were probably double those for women at any point before the 1920s. Although literacy rates increased quickly before 1917, overall literacy in Soviet Russia still remained low, making Likbez necessary.

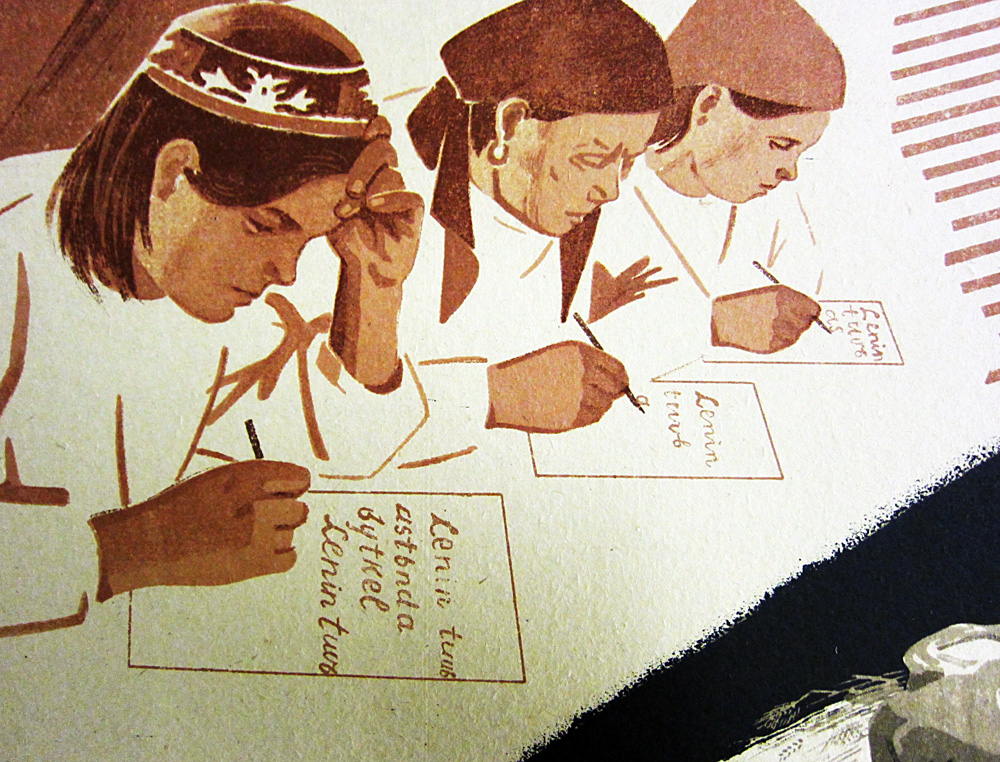

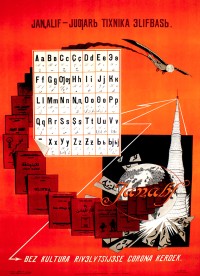

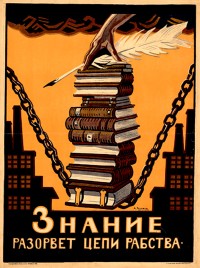

The Soviet leadership under Vladimir Lenin considered Likbez a tool for “giving the entire population . . . the opportunity for conscious participation in the country’s political life,” a way to combat rumor and gossip. For others, Likbez was a way to stimulate modernization and mass culture. The 1919 decree established tens of thousands of literacy stations teaching in Russian or, for non–Russian speakers, in a native language. The decree assigned responsibility for the campaign to Narkompros, the People’s Commissariat of Education.

From 1920 onward, Narkompros managed the campaign via its “Extraordinary Commission for Likbez,” evoking the name of the political police, “the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage.” By one count, late in that year the Narkompros commission was running over 12,000 stations teaching some 287,000 people. The trade unions and other organizations also joined. Measures of effectiveness changed over time, but a general upward trend was noticeable. Previously, citizens who understood the alphabet and could read their own name were classified as literate. Under the Likbez campaign, an individual became “semi-literate” after six to eight hours a week of study over three months, at which point another six to eight months of study would bring a person up to full literacy. By 1926, Red Army recruits classed as literate were expected to read printed materials.

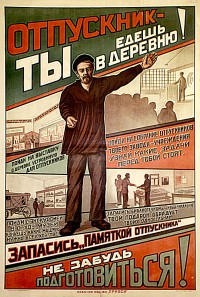

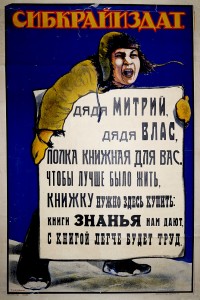

In 1923, a Narkompros plan called for the trade-union members to achieve full adult literacy by May Day 1925, while the Extraordinary Commission was to redouble efforts among the population at large, targeting full literacy by the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. In rural areas, reading rooms were stocked with posters, pamphlets, and books specifically designed to foster both literacy and familiarity with the basics of Soviet ideology. Yet Likbez often suffered from a lack of support by state and local party leaders, a lack of instructors, and a paltry budget – its share of the Narkompros budget fell over time – combined to limit even modest success by the mid-1920s. Compounding this, when the 1921–22 famine struck the Volga region, literacy stations, workers’ clubs, schools, and other outlets shut down.

Likbez campaigns lost steam after the Extraordinary Commission and the trade unions missed the target set for October 1927. Instead, resources and attention flowed to technical and higher education plans forming part of the epochal industrialization and collectivization efforts during Stalin’s First Five-Year Plan (1928–32). Despite budget shortcomings and missed targets, the campaigns by Narkompros did in fact bear fruit. Statistics suggest a significant achievement: by 1926, overall literacy had surpassed 50 percent and in most categories it increased 10 percent from pre-1917 levels, even though the gender gap remained. According to the 1939 census, nearly 90 percent of those from school age to 49 years old were literate and the gender gap, while not eliminated, had closed significantly.

Suggested Reading and Resources

“Liquidation of Illiteracy,” January 29, 1919 at Seventeen Moments of Soviet History, http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/raising-socialist-youth/raising-socialist-youth-texts/liquidation-of-illiteracy/

Charles E. Clark, “Literacy And Labour: The Russian Literacy Campaign within the Trade Unions, 1923-27,” Europe-Asia Studies 47, no. 8 (1995), 1327–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139508412323.

Charles E. Clark, Uprooting Otherness: The Literacy Campaign in NEP–Era Russia (Selinsgrove, Pa.: Susquehanna University Press, 2000).

Ben Eklof, Russian Peasant Schools: Officialdom, Village Culture, and Popular Pedagogy, 1861–1914 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

Lenore Grenoble, Language Policy in the Soviet Union (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003).

Peter Kenez, The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917-1929 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985)..

![PP 139: Only soviet rule can lead working masses to light and enlightenment.

[Posted by] the Club Section of the Extramural Department of the Commissariat of Public Education.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-139/pp139-200x299.jpg)

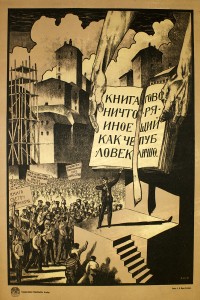

![PP 388: State Publishing House [address illegible] Books on all branches of knowledge](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-388/pp388-200x284.jpg)

![PP 472: [Upper right corner]

Literacy Day.

April 24-26

May 7-9

1918

[From the man’s mouth]

Comrades and citizens!

Make your contribution in promoting literacy!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-472/pp472-200x150.jpg)

![PP 623: 1917-1927 The work of ideologically based education.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-623/pp623-200x158.jpg)

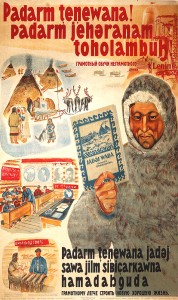

![PP 625: The October Revolution gave all people of the soviet country the opportunity to build a new, good life – socialism. The October Revolution liberated people of the north from the yoke of merchants, kulaks and shamans. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-625/pp625-200x284.jpg)

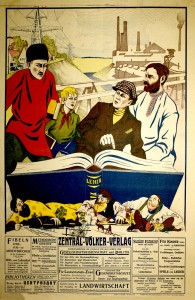

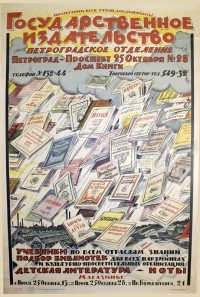

![PP 731: GOSIZDAT

Subscriptions for the year 1928 are available.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-731/pp731-200x133.jpg)

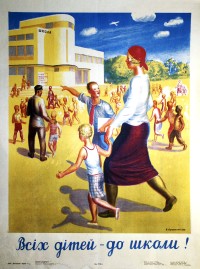

![PP 788: Only children of capitalists were admitted to bourgeois schools…

They and only they always had their tasty breakfast.

The United School of Labor has opened wide its doors to all little citizens of Soviet Russia.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-788/pp-788-catalog-image-200x238.jpg)

![PP 792: Organize Country Houses of Reading.

Learning is Light. Ignorance is Darkness. Knowledge is Power.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-792/pp-792-catalog-image-196x300.jpg)

![PP 793: Organize Country Houses of Reading.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-793/pp-793-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 804: Down with ignorance and backwardness!

[Panel 1]: Krasnoarmeets! The illiterate are fooled by priests, dukes and other dark forces without even noticing it.

[Panel 2]: But no force can be your master if you are educated and knowledgeable.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-804/pp-804-catalog-image-200x129.jpg)

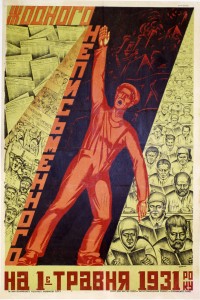

![PP 805: Let Us Eliminate Illiteracy!

By the 10th Anniversary of the October Revolution.

All illiterates, eradicate illiteracy in school! All literates in society [say] “Down with illiteracy.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-805/pp-805-catalog-image-200x267.jpg)

![PP 915: The life of the literate.

There lived an illiterate peasant.

He did not read clever books.

Life led him nearly to tears,

Every day everything was a bad break! Every day he toiled for nothing,

Life carried him along, like a blind person! He could not read a page,

About how to plow his land.

And his labor brought

In very scanty crops!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-915/pp-915-catalog-image-200x129.jpg)

![PP 961: Have you signed up?

[Get] 9 free prizes in 9 months.

Subscriptions now available January 1, 1925 - October 1, 1925

to the “Workers’ Newspaper”.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-961/pp-961-catalog-image-200x287.jpg)

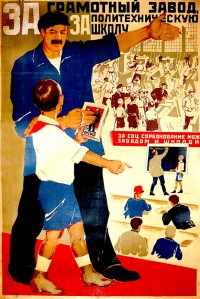

![PP 989: Proletarian, in Institutions of Higher Education, Technical Schools, and Retraining Courses – This Is the Path to Creating Proletarian Cadres. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-989/pp989-181x300.jpg)

![PP 1051: Every peasant needs to subscribe to the peasant newspaper "Soviet Village". Every month, each subscriber will receive all issues of the newspaper and one supplement... [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1051/pp1051-200x270.jpg)

![PP 1080: Komsomol’skaia Pravda begins correspondence courses on the theoretical study of fundamental questions of Marxism–Leninism. The entire correspondence course is expected to last 6 months and will encompass fundamental questions of Marxism–Leninism. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1080/pp1080-200x283.jpg)

![PP 1171: Young proletarians to Enlightenment and Knowledge!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1171/pp-1171-catalog-image-200x258.jpg)

![PP 1177: Power of Labor continues accepting newspaper subscriptions for 1928. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1177/pp-1177-catalog-image-200x262.jpg)

![PP 1178: Library

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1178/pp-1178-catalog-image-200x134.jpg)