Comecon-Warsaw Pact

Victory in World War II posed new challenges for the Soviet Union. Josef Stalin, his country devastated by two wars with Germany in two generations, sought security via a buffer. By 1945, the Red Army occupied Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and the entire Eastern section of Germany. Independently, communist partisan movements in Yugoslavia and Albania had set up initially pro-Moscow governments. Each country's trajectory was a variation on a theme. Communist parties joined coalition governments with other antifascist forces. [Text continues at bottom of page]

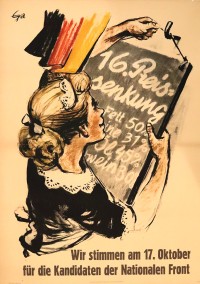

In each coalition, non-communist partners filled offices possessing formal power, but communists controlled internal security and the police. Using these repressive apparatuses, the communists denounced opponents---even those with formidable antifascist credentials---as Nazi collaborators, silenced dissent, disbanded organizations, and rigged elections.

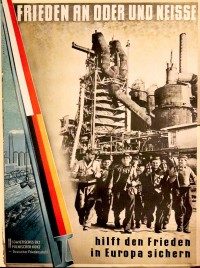

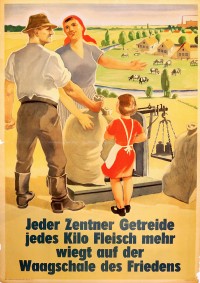

Amid mounting Cold War tensions, Stalin replaced each coalition with a communist party dictatorship. Those tensions rose because Stalin rejected participation in U.S.-led plans for the postwar world economy and he pursued an independent policy in jointly occupied Germany. In March 1946, former Prime Minister Winston Churchill argued that an "iron curtain" had divided Europe. Wary, U.S. leaders aided anti-communist governments in Turkey and Greece. In June 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall announced a plan of economic aid to Europe designed to alleviate the desperation born of wartime ruin. In October 1947, communist parties in Eastern Europe and in western democracies met to respond to the Marshall Plan. They founded the Communist Information Bureau, or Cominform, a coordinating body with limited capacities. Thus, countries under Stalin's sway declined the U.S. assistance plan, although the remaining coalition in Czechoslovakia briefly hesitated. In February 1948, Czechoslovak communists staged a coup, signaling the end of Stalin's coalition policy. That summer, the Cominform expelled Yugoslavia due to the independent-minded leadership of Josip Broz Tito. The country was re-admitted in 1964 but only via special agreement. In January 1949, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania formed the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, or Comecon, which forbade its members from participating in the Marshall Plan and U.S. global economic framework. Its founding members were joined by East Germany and Albania---that stopped participating in 1961 out of loyalty to China, and formally withdrew in 1987---and, in later years by Mongolia, Cuba, and Vietnam.

Although weak, the Cominform and Comecon gave structure to informal links between Moscow and what they called the "people's democracies" of Eastern Europe. The junior partners exercised some influence, but Moscow dominated economically and militarily. In moments of uncertainty, some leaders and peoples tested the relationship's boundaries, occasionally inviting disaster. When Stalin died in 1953, his successors confronted labor unrest in East Germany that, although quickly suppressed, convinced them that change was needed.

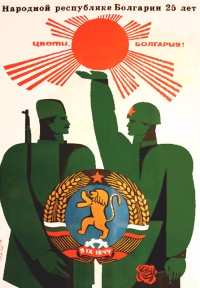

Stalin's heirs forced hardline leaders to make concessions and even cautiously reopened relations with Yugoslavia, which continued to follow its own path. In 1955, they found themselves facing the prospect that West Germany was to re-arm and join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the NATO military alliance. The Soviet Union and its allies therefore founded an alliance of their own, the Warsaw Pact. By denouncing Stalin's crimes in February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev raised the question of how far de-Stalinization was to go. In Poland, popular protests against the hardline leadership led Soviet leaders to broker a compromise bringing reformists to power. In Hungary, the process initially appeared similar spun out of control. The new Hungarian leaders limited repression and curbed abuses, moves accepted by Moscow. However, simmering tensions and anti-Russian sentiment burst out in street protests in Budapest leading to directions the new leadership had not expected. When the Hungarians moved to end the party monopoly and withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet Army moved in to crush the revolution. This did not end the trend of moderation in the region relative to the Stalinist past, but it did indicate how much political change would be tolerated. By contrast, Czechoslovakia changed little after 1956. When reformists inside the party led by Alexander Dubček finally achieved power in early 1968, they launched initiatives that won wide approval. The Soviet leadership under Leonid Brezhnev tolerated this first phase, which lasted into the spring. However, when changes threatened to escape party control, the Soviet Union brought in the army in August 1968, asserting its right to intervene, a policy subsequently known as the Brezhnev Doctrine. Pursuing an independent policy after 1968, Romania under Nicolae Ceaucescu never broke ties, but also refused to be predictable.

The threat of military intervention did not prevent instability. In the early 1970s, the authorities suppressed major labor unrest in Poland, which emerged again in 1980 amid economic downturn. Protests in the shipyards of Gdansk led to the formation of Solidarity, an independent trade union unique to the Soviet sphere, and therefore threatening to communist rule. Weakened, the Polish government negotiated, but soon the spreading popular movement threatened to incur Soviet intervention. Polish leaders imposed martial law, arrested activists, and drove Solidarity underground. Yet it remained there ready to reemerge when Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms forced change on communist parties across Eastern Europe. In 1989, Hungary opened its borders and Solidarity negotiated a peaceful transition in Poland. In other places, leaders hesitated to reform and invited mass direct action. Hundreds of thousands filled Wenceslas Square in Prague in what became known as the Velvet Revolution. Crowds demolished the Berlin Wall after the East German police refused to maintain control. In Romania, the Ceaucescu dictatorship fell violently, resulting in his capture and, after a brief trial, summary execution. Gorbachev's decision to allow the Communist Bloc nations to go their own way ended Cold War tensions, making the abolition of Comecon and the Warsaw Pact in 1991 a mere formality.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Paulina Bren, The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism after the Prague Spring (Cornell University Press, 2010).

Timothy Garton Ash, The Magic Lantern: The Revolution of '89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin, and Prague (Vintage, 1999).

Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (Penguin, 2006).

Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, "International" http://soviethistory.msu.edu/theme/international/

![PP 814: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-814/pp-814-catalog-image-200x267.jpg)

![PP 828: Sell your fruits at the local agricultural cooperative.

Cherry, sour cherry, apricot, plum, apple, pear, grape, walnut, almond.

Have a sales contract [and] you will have a higher income.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-828/pp-828-catalog-image-200x267.jpg)

![PP 841: Long live August 20, our holiday celebration!

[On the book] The Hungarian People’s Republic is the state of the workers and the working peasants. In the Hungarian People’s Republic the working people own all power. The Hungarian People 's Republic provides its citizens the right to work and the compensation for that work according to the quantity and quality of work.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-841/pp-841-catalog-image-200x149.jpg)

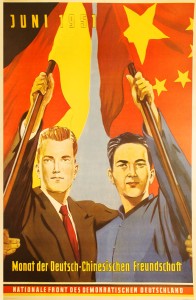

![PP 853: Friendship forever.

Month of German-Soviet Friendship.

National Front of Democratic Germany [East Germany].](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-853/pp-853-catalog-image-200x291.jpg)

![PP 854: 1st draw of the 2nd peace loan.

Every forint invested in the national loan will return ever so much!

Draw [held in] Budapest, Music Academy. September 18, 19, 20, 21, 1952.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-854/pp-854-catalog-image-200x267.jpg)

![PP 886: “The power of 5 million”

A traveling exhibition of the FDGB [Federal Board of the Free German Trade Union]

Exhibition Hall -- City Museum

from April 4 to 10, 1949. Daily 2pm to 7pm.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-886/pp-886-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 978: There: elections are directed by monopolistic American agents.

Here: free elections [are held] such as never before during the bourgeois regime.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-978/pp978-200x124.jpg)