Communist Culture

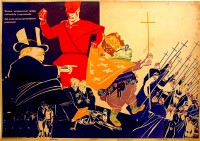

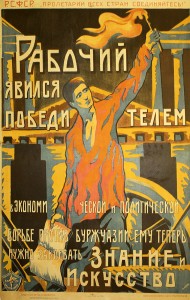

During the initial rise of Soviet administration in the government there was a heightened period of productivity among almost all Russian artists. New endeavors and changes took place immediately following the Russian Revolution as the Soviet government boldly split with the past (politically and socially) to build a modern, socialist future. With the arts in particular, there was an increase in its modern forms as the conservative, traditional styles of the past were side stepped due to their cultural ties to Tsarism. [Text continues at bottom of page]

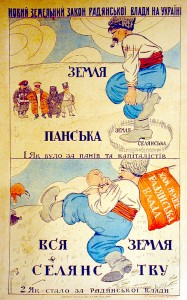

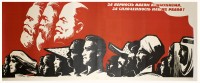

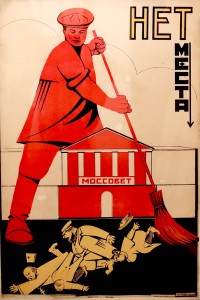

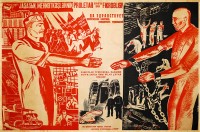

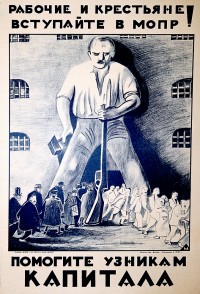

State-initiated closures of the Imperial art schools and academies brought new, state-sponsored free art workshops, people’s museums, traveling exhibitions and revolutionary arts festivals. However, during and after the Russian Revolution of 1917 the atmosphere of artistic change fostered competing cultural currents. The cultures of mainstream and radical art both fought for acceptance and artistic dominance in the fledgling Soviet Union. In the end, nearly all artists lost the fight. Government regulations piled-on a host of political safeguards for painting, sculpture, graphic design, the visual arts, music and the written and spoken word. Before the safeguards became commonplace in Soviet society, the Proletarian Culture movement called Proletkult advocated a completely new future built by and for workers. Their mission radically challenged some of the party elites' preference for more traditional art forms. By the 1920s, the avant-garde movement formed a base for yet another revolutionary art movement in Russia-- constructivism.

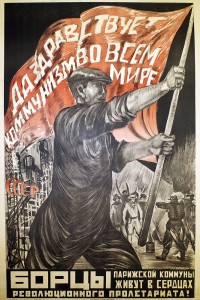

At the core of its ethos, constructivism upheld functional form without adornment as a way socially advance. Artists such as Alexander Rodchenko built workers' clubs, public-transit garages, housing and other structures that sharply broke with traditional, Russian architecture precedents. The poet and graphic artist Vladimir Mayakovsky created propaganda posters, book designs, and forward-looking advertisements. The film director Dziga Vertov produced experimental motion pictures that were groundbreaking for their cinematography and editing while other constructivist-era artists challenged traditional motifs in photography, theater and other mediums.

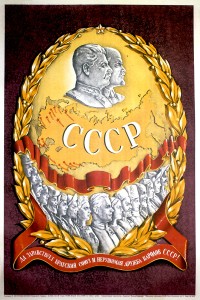

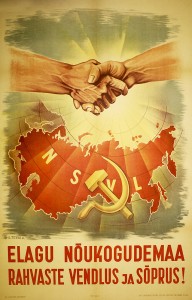

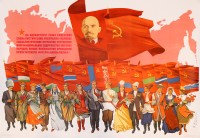

Stylistically, at the center of Soviet culture was the color red. It was not a contemporary shade by any means. For Russians the word krasnaia means “red” but it also can mean “beautiful”. Red is linked to life as with the color of blood and it is a symbolic color for the sun. Soviet audiences likely embraced the motif of the red banner of socialism partly because its color was also long-associated with iconography in the Russian Orthodox Church. While the Soviet elite treated religion as a pariah they had their citizens assemble a "red corner" in their home and/or workplace with a modern icon of Vladimir Lenin, the revolution’s founding father.

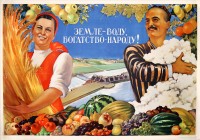

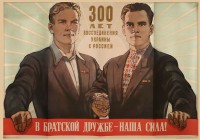

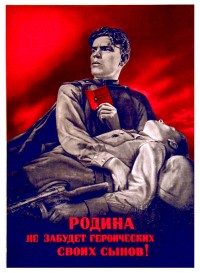

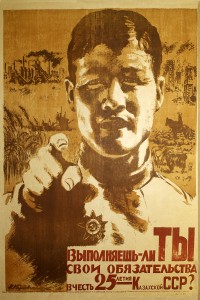

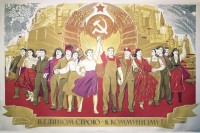

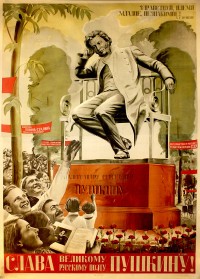

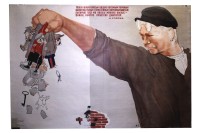

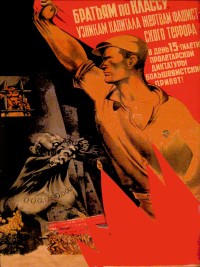

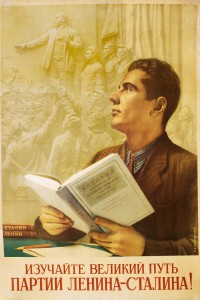

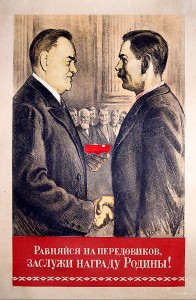

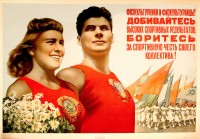

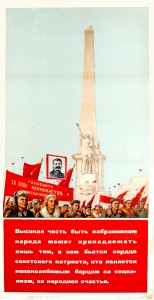

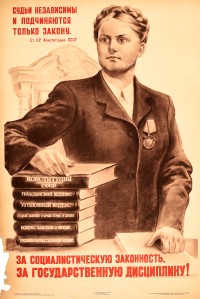

During the First Five Year Plan (1928--32), the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP) and other critics claiming to speak on behalf of the working class denounced both pre-revolutionary culture and the avant-garde of the 1920s as inaccessible. They assaulted imported culture as emblematic of the permissiveness of the era of the now-rejected New Economic Policy, ending imports of films and stifling Soviet Russia's fleeting jazz age. Later scholars described this as a "cultural revolution," an anachronistic term nonetheless appropriate to cultural transformation under Josef Stalin. By 1932, Stalin intervened to impose uniformity. Dissatisfied with both the avant-garde and the cultural revolutionaries, he delegated authorities to impose an ideal accessible to the masses, socialist in content, and based on domestic precedents. Audience response was subsumed by these functionaries' efforts to create political art with appropriate socialist themes. Government officials seized editorial boards and set up institutions to impose Socialist Realism in the arts and literature. It was realism only in that it dealt with themes of everyday life, while writers and artists avoided depicting the messy realities of the present and instead envisioned not what was, but what should and was, ideally, soon to be.

Themes of factories, industrial progress, mines, and collective farms predominated, while zealous communist heroes--workers, engineers and collective farmers-- were appropriate to these settings. The quality of work suffered as talented writers remained silent out of fear from political persecution and visual artists turned out prescribed material. Socialist Realist works proved popular with the masses because they fit the spirit of the age by praising achievements made on Stalin's benevolent watch---and because they faced no competition.

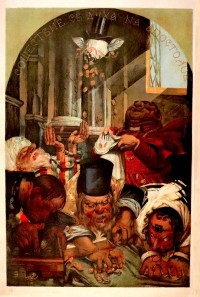

The conservatism of the 1930s continued into the 1950s, when nonconformist attitudes came under renewed attack in the early Cold War years. Paralleling the red scares sweeping the United States, campaigns against "rootless cosmopolitanism" in the arts, science, and other endeavors besmirched anyone with connections to international communities. Owing to the anti-Semitic atmosphere, suspicion often fell on anyone of Jewish origin. When Stalin died in 1953, communist culture seemed locked in ice. Yet later that year, writers began to attack Socialist Realism's aesthetic and moral flaws: one-dimensional heroes, caricatured antagonists, and simplistic conflicts. In elite literary journals, they demanded "truth" and "honesty." In 1954, Ilya Ehrenburg published his epochal novel The Thaw, which unleashed a stream of new literature. Replacing the certainties of previous patriotic war films, new cinema began to question personal relationships, morality, honor, and other difficult, previously taboo topics. Extraordinarily, Alexander Solzhenitsyn was allowed to publish One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a novel whose hero navigated the Gulag's enclosed world of depravity and moral ambiguity. Although still subject to official approval, officially sanctioned translations of literature and other influences from abroad, even the West, began to slowly appear.

Socialist Realism's passing did not signal unchecked liberalization. Refused publication in the Soviet Union, Boris Pasternak's novel Doctor Zhivago appeared in Italy and won the 1958 Nobel Prize for Literature. Nikita Khrushchev denounced its interpretation of the revolution and persecuted the author. The atmosphere grew more repressive after Khrushchev fell in 1964. His successors tried and convicted Andrei Siniavskii and Iulii Daniel for having published works critical of Soviet society abroad under pseudonyms. Underground, works of startling expression circulated in samizdat, or "self-published" materials all painstakingly copied on typewriters. Artists who by day created official art, advertising, and other work used the materials at hand to create by night nonconformist works rarely seen in public.

Official high culture remained conservative, but excelled in classical music and ballet. Occasionally, innovative works such as the films of director Andrei Tarkovskii were shown, but only in a few domestic theaters even though they earned international fame. Popular success went to epic war films, a movie about an amphibian-man, and a TV series detailing the fictionalized exploits of a Soviet agent inside the Nazi regime. Popular music remained restricted in form and content, while underground singer-songwriters such as Vladimir Vysotsky thrived, word of them spread on copied cassette tapes. Since the 1950s, music lovers had circulated Western rock n' roll records copied onto used x-ray plates, an innovation that brought the Beatles into Soviet apartments.

After 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of glasnost, or "openness," brought a wave of foreign popular culture into the Soviet Union. Having been confined to the underground during the 1970s and early 1980s, rock music using Russian lyrics and appealing to Russian sensibilities burst into the open. Banned films appeared in cinemas. Readers could purchase books by Solzhenitsyn and other exiles and they could freely obtain literature written decades prior that once had little chance of publication. Glasnost also eliminated the state's domineering control over the arts. While the late-1980s was viewed as a period of cultural freedom to a segment of the Soviet populace it was also alienating generations of Soviets who were comfortable with the familiar system of their recent past.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Jeffrey Brooks, Thank You, Comrade Stalin! Soviet Public Culture from Revolution to Cold War (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia (Cornell University Press, 1992).

Mosfilm (Soviet Films with English subtitles) https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL4dWJMOQ_a1TgayrpaB-SEVJhHC58U1wU

Pete Paphides, "Bone Music: The Soviet Bootleg Records Pressed on X-Rays," The Gaurdian, January 29, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/jan/29/bone-music-soviet-bootleg-records-pressed-on-xrays?CMP=share_btn_link.

Seventeen Moments of Spring, "Literature" http://soviethistory.msu.edu/theme/literature/.

Sasha Raspropina, "Rock in the USSR: New Photos of the Leningrad Underground during Perestroika," https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/6563/igor-mukhin-leningrad-photos-perestroika-viktor-tsoi

Richard Stites, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution

(Oxford University Press, 1991).

Richard Stites, Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society since 1900 (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

![PP 116: KPSS [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] our strength is in unity!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-116/pp116-200x133.jpg)

![PP 180: We are for peace!

[Song lyrics] “We are for peace! And we will carry this song to our friends around the world!”](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-180/pp180-200x300.jpg)

![PP 292: On every dollar there is a piece of dirt, income from sale of weapons... On each dollar there is a trace of blood.

-- [Vladimir] Lenin](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-292/pp292-200x296.jpg)

![PP 386: [Left] State symbol of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics

[Middle] Moscow, capital of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics

[Right] State flag of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics

[Banner at bottom] Glory to the Motherland of October!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-386/pp386-200x109.jpg)

![PP 406: Kulak Son of Kulak has a big, fat belly, his pig’s face is huge and, as it is supposed to be, with a beard like a shovel. His house has expensive furnishings inside and during the revolution he was collecting various reparations from barons’ houses. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-406/pp406-200x173.jpg)

![PP 468: The Workers’ Club is the Hearth of Revolutionary Thought. [Bottom left] Club Section of the Extramural Department of the Commissariat of Public Education.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-468/pp468-200x297.jpg)

![PP 597: About Revitalized Icons and about how a Building Manager Revitalizes Ever-Active Priests

[On top left]

Three peasant spiders are gathered

to warm themselves and to treat

their bones to steam around

a huge samovar.

You will recognize all of them

when you look. All of them are your friends,](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-597/pp597-200x300.jpg)

![PP 599: Expose Sectarian Activities with the Pen of the Worker-Correspondent and the Light of Science!

[Text at bottom]

Here is the “head” of the sects …

Don’t hurry toward this, —

They will undress you in a tricky way

for the sake of “saving your soul”.

They look around in a gentle, downcast way,

their voice is as soft as silk,

but until now, the spiteful wolf

has been covered in sheep’s clothing!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-599/pp599-200x268.jpg)

![PP 790: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-790/pp-790-catalog-image-200x127.jpg)

![PP 807: Priestly Sophistry- A Weapon of the Enemy.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-807/pp-807-catalog-image-200x284.jpg)

![PP 810: Religion -- an obstacle to the Five Year Plan. [partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-810/pp-810-catalog-image-200x143.jpg)

![PP 1073: Only in the Soviet Union are Jewish people given the right to the land and to voluntary labor.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1073/pp1073-200x287.jpg)

![PP 1078: Cinema- The Most Popular Form of Art!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1078/pp1078-200x143.jpg)

![PP 1137: Subscribe to Pathway to Health for 1927.

A monthly worker-peasant magazine dedicated to issues of healthcare and medicine.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1137/pp-1137-catalog-image-200x269.jpg)