Cold War

The Cold War was a geopolitical conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, whereby each nation professed their totalizing ideology held the blueprint for society, politics, economics, science, culture, and more. The Cold War shaped participants' thinking about the world, dividing it into superpower-led blocs of allies representing polar opposites. Despite frosty official relations before World War II, the Soviet Union and United States forged an alliance against Nazi Germany. [Text continues at bottom of page]

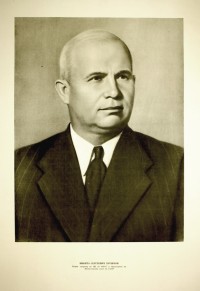

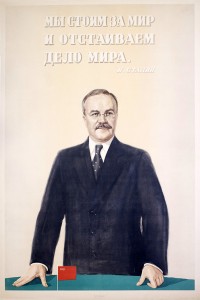

By war's end in 1945, however, each side considered its interests incompatible with the actions of the other, making conflict overwhelmingly likely. To further their respective interests, neither Soviet leader Josef Stalin nor United States President Harry Truman was ready or able to negotiate a compromise. Stalin sought security by installing friendly regimes on the Soviet Union's western borders with Europe in countries occupied by the Red Army in 1945. Yet Stalin was constrained by relative weakness caused by wartime losses. In addition to possessing a monopoly on the atom bomb, the United States emerged from the war as the world's financial and industrial power. It established the Bretton Woods system, an international framework for facilitating trade, investment, and---policymakers hoped---democracy. The Soviet Union opposed this and, furthermore, was seen by United States leaders as an ideologically alien threat.

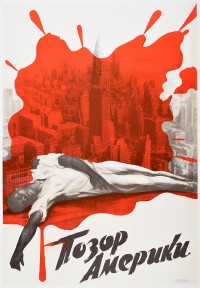

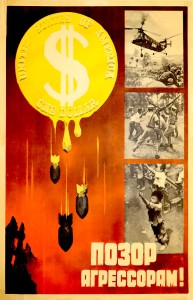

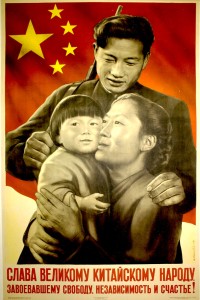

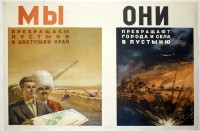

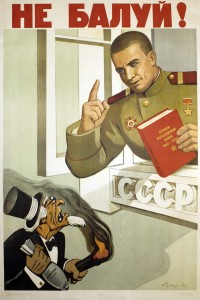

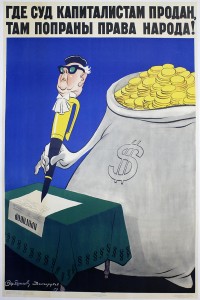

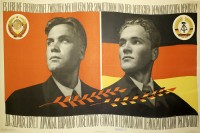

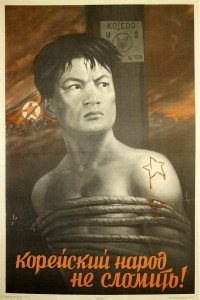

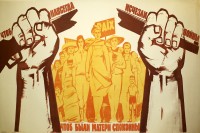

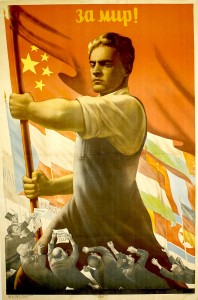

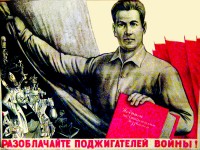

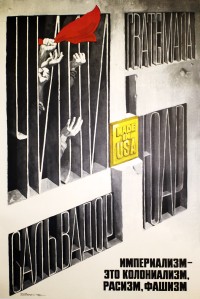

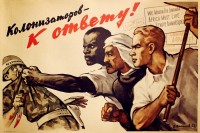

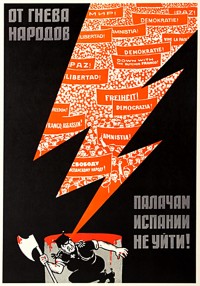

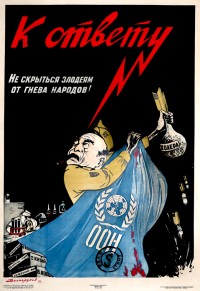

Conflict arose where their spheres of influence adjoined. In early 1947, United States officials grew fearful of threats to Greece and Turkey. In 1948, Stalin consolidated his hold over Eastern Europe while the United States extended Marshall Plan aid to western countries. Fueled by the division of occupied Germany, the smoldering conflict heated up when Stalin blockaded the western powers' access to their part of Berlin. Then the struggle went global. In 1949, communists won China's long-running civil war. In 1950, North Korea attacked the South. From 1946 to 1954, the United States and Soviet Union quietly backed opposing sides in the ongoing anticolonial war in Vietnam, a precursor to the United States intervention there in the 1960s. At home, both the United States and USSR experienced panic about internal subversion by disloyal individuals and groups. Anti-communist crusades in the United States within the government and private sectors were paralleled in the USSR by officially sanctioned attacks on "rootless cosmopolitans," a campaign with anti-Semitic themes against anyone with foreign connections. While citizens in the United States demonized "the Reds," Soviet audiences learned to hate the militarist, imperialist capitalists portrayed as having secretly been in league with the Nazis.

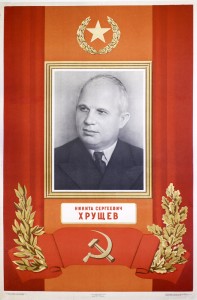

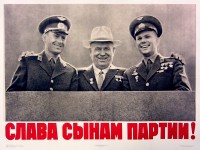

After Stalin died in 1953, his successors seized opportunities to relieve tension, but relations between the two nuclear-armed superpowers remained guarded. In 1955, leaders sat at the negotiating table in Geneva for the first time in a decade. Nikita Khrushchev called for competition in science, industry, and living standards, de-emphasizing the arms race by making much rhetorically of his country's small number of missiles. Confident that history was on his side and emboldened by the impressive growth rates, Khrushchev pledged that his country would soon "catch up to and surpass America" in economic measures.

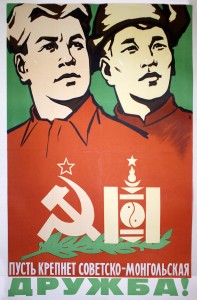

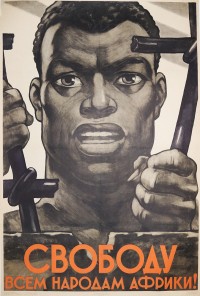

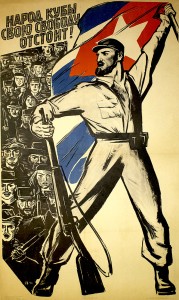

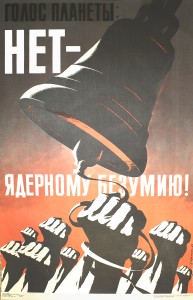

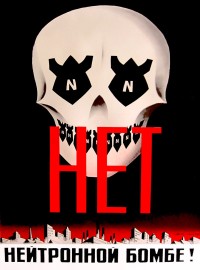

He opened relations with former colonies newly independent from Great Britain, France, and the other European empires. Soviet influence in Africa, Asia, and Latin American remained limited, but the initiative began a new arena for economic, political, and military competition. Inheriting a weaker strategic position, Khrushchev pressed tactical advantages in hotspots such as Berlin and Cuba. The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, having taken the world to the brink of nuclear war, chastened both sides. In 1963, the United States and the USSR improved communication by installing a direct line between the Kremlin and the White House and signed a treaty limiting nuclear testing.

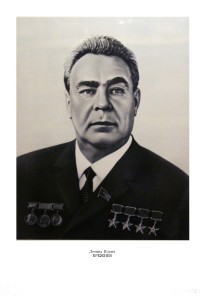

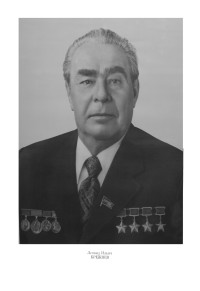

By the late 1960s, the USSR had developed nuclear parity with the United States. Both possessed weapons sufficient to ensure that enough would survive a first strike to destroy the aggressor---and likely the world. This second-strike capability made real the principle of mutual assured destruction, or MAD, a grim balance of terror that actually deterred conflict and enabled Détente, a period of relaxed tensions leading to intensive diplomatic negotiations and substantive agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union. Each superpower sought to navigate a world that had become multipolar. Long enjoying United States military protection, West European countries began to act assertively by reaching out to the USSR politically and economically. Having broken with the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China developed a nuclear deterrent and emerged from isolation onto the international arena. Desperate to escape the quagmire in Vietnam, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger sought agreements with the Soviet Union under Leonid Brezhnev. They signed nuclear arms limitations treaties and the Helsinki Accords, which provided the Soviet Union and its allies with assurances about postwar borders and internal sovereignty in return for the introduction of the language of human rights into international relations.

Yet Détente proved unpopular and short lived. For the Soviet leaders, it settled relations with the United States and stabilized Europe, but did not preclude either nation from taking action in other regions. For example, in the late 1970s, each nation backed opposing sides in sub--Saharan Africa conflicts. Then, in 1979, the USSR sent its military into Afghanistan to defend a threatened friendly government. Interpreting this as aggression, the Carter administration turned firmly against Détente. Furthermore, the Afghanistan conflict emboldened the American hardliners who attacked Détente as appeasement, rhetoric that aided the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. In 1983, the Soviet Air Force downed a civilian Korean Airlines plane and, later that year, a provocative NATO military exercise brought fears of nuclear war back to the fore.

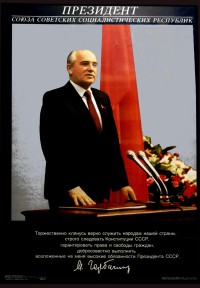

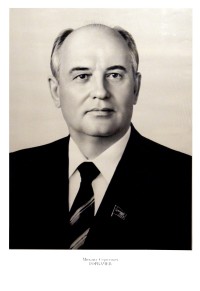

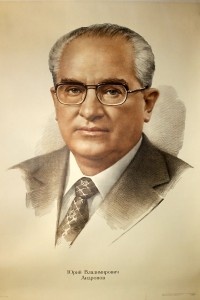

Then, just as suddenly as renewed tensions flared, the Cold War ended. Becoming General Secretary in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was faced with the true proportions of the USSR's military-industrial complex. Inheriting an under-performing economy and unwilling to continue the costly Afghan War, he was determined to reform the USSR in order to save it. He sought negotiations with the United States and its allies, finding that President Reagan, was open to direct talks. In a string of summit meetings, arms reduction treaties, and official visits, the two leaders redefined superpower relations.

In October 1989, Gorbachev responded to the electoral victory of Solidarity, Poland's independent trade union, by explaining that the Soviet Union had abandoned the Brezhnev Doctrine, which asserted its right to intervene militarily in its allies' internal affairs. Populations ruled since 1945 by seemingly ironclad communist states quickly rejected one-party rule and broke from Soviet influence. In 1990, Germany reunified, ending the division at the heart of Europe and closing the Cold War more than a year before the Soviet Union dissolved.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, Khrushchev's Cold War: The Inside Story of an American Adversary (W. W. Norton, 2006).

Library of Congress, "Revelations from the Russian Archives," https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/archives/sovi.html

Serhyi Plokhy, Yalta: The Price of Peace (Viking, 2010).

Seventeen Moments of Soviet History, "International" http://soviethistory.msu.edu/theme/international/

Vladislav M. Zubok, A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov, Inside the Kremlin's Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev (Harvard University Press, 1996).

![PP 088: The good of the nation-The Law of Socialism. There is no exploitation, oppression or unemployment under socialism! [Right panel with U.S. worker] Exploitation, oppression, unemployment–The Wolfish Law of Capitalism. This is reality for millions of workers in capitalistic countries...](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-088/pp088-200x133.jpg)

![PP 124: [The United States is] Marching too far – Their heads will be broken!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-124/pp124-200x68.jpg)

![PP 291: [On panel showing the Soviet female student] In USSR: In 1951-1955 the construction of urban and rural schools will increase by 70% in comparison with the previous 5 year plan.

[On panel showing the U.S. male student] In USA: The budget provides 1% for education and 74% for military expenditures. There are over 10,000,000 illiterate people in the USA. About one-third of American children do not attend school.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-291/pp291-200x300.jpg)

![PP 367: Vietnam

[On newspaper of Pravda, held by the man]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-367/pp367-200x106.jpg)

![PP 449: 10 Years of the German Democratic Republic [GDR]

Brotherly greetings to the G.D.R. workers who are building socialism!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-449/pp449-200x133.jpg)

![PP 818: These are “Human Rights” in the Capitalist World.

128.4 billion dollars – budgeted by the USA, the chief citadel of capitalism, during fiscal year 1979 for military purposes. This includes nuclear, thermonuclear, and neutron bombs, “flying fortresses,” and airborne rockets: the blood and tears of millions of people. [partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-818/pp-818-catalog-image-200x147.jpg)

![PP 1063: [Left panel] There: lack of rights, unemployment, poverty. [Right panel] Here: Equality in rights, freedom, well-being.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1063/pp1063-200x132.jpg)