World War II

The Second World War defined the generation that fought and struggled in it. Long before Adolf Hitler ordered his army to invade the Soviet Union, the nation had been preparing for war. During the first two Five-Year plans (1928-32 and 1932-36), breakneck industrialization augmented capacity to manufacture tanks, planes, and other necessities of warfare. In the 1930s, education and extracurricular activities in paramilitary training prepared Soviet youth. Josef Stalin monitored rising fascism and militarism in Europe and East Asia, and the events of the Spanish Civil War in particular. When war came, however, it was triggered in part by Stalin's strategic choices. [Text continues at bottom of page]

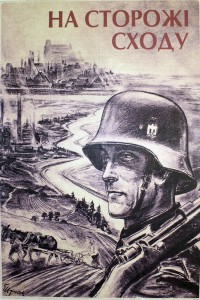

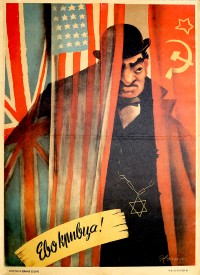

Distrusting the leaders of France and Great Britain, who had conceded Czechoslovakia's independence to Hitler at Munich in September 1938, Stalin sought to buy time by signing a non-aggression pact with Germany in August 1939. That pact green-lighted Hitler's occupation of western Poland and it triggered war with Great Britain and France, but it also handed eastern Poland to the Soviet Union.

On a strategic level, Stalin miscalculated by expecting Hitler's attack to come only after Great Britain had, like its French ally in 1940, been knocked out of the war. On a tactical level, Stalin dismissed reports of an impending German attack, more fearful that some local skirmish might escalate into war. The Red Army also embraced military doctrines based on repelling a foreign incursion as a prelude to counterattack destined to spread revolution westward. In addition, Stalin's purges of Red Army leadership in the mid-1930s crippled its officer corps and decimated the positions formerly held by experienced military leadership. Therefore, the Red Army was completely unprepared when Axis soldiers poured across the border in the predawn twilight of June 22, 1941. In the first few hours, German planes destroyed Soviet aircraft on the ground, massed in tight peacetime formations. Within weeks, the Germans encircled entire armies of Soviet troops, killing many and capturing the rest, most of whom would not survive the German prisons where they were sent.

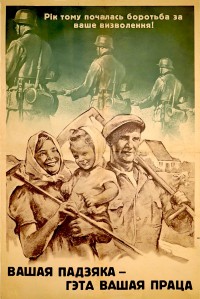

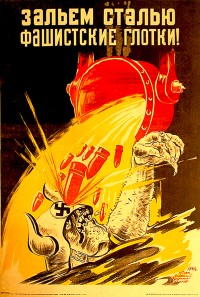

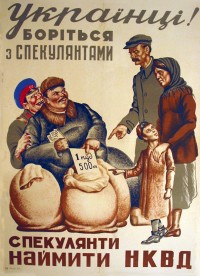

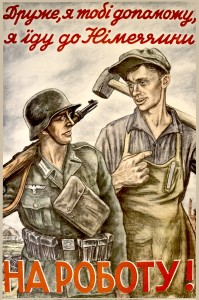

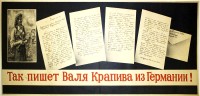

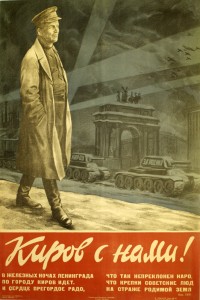

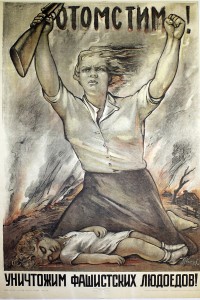

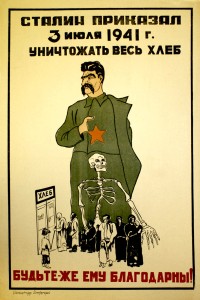

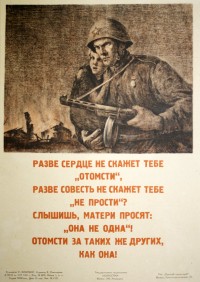

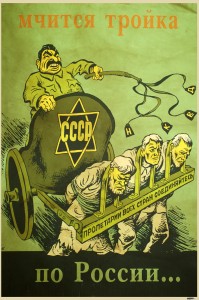

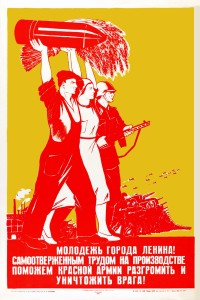

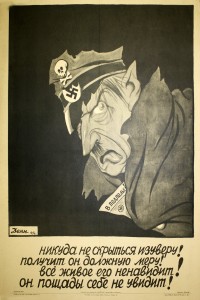

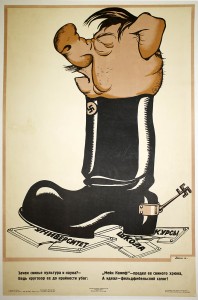

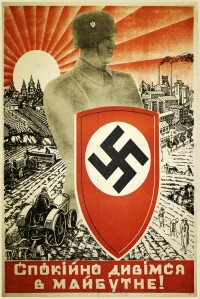

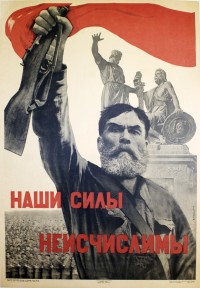

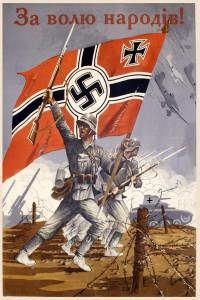

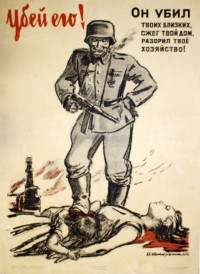

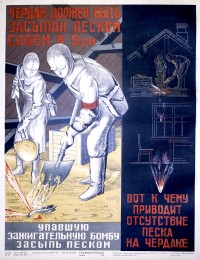

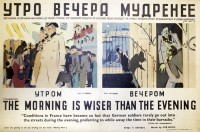

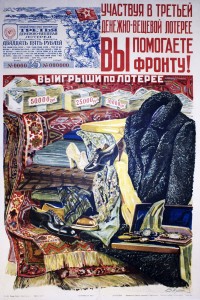

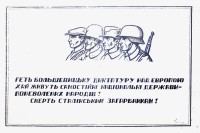

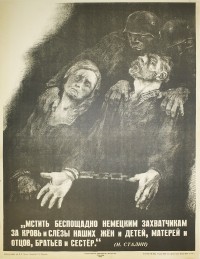

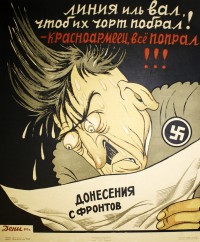

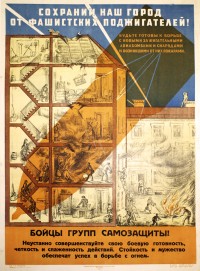

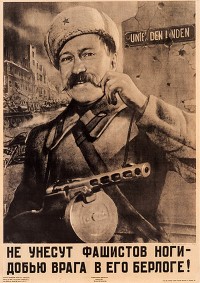

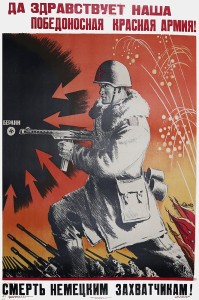

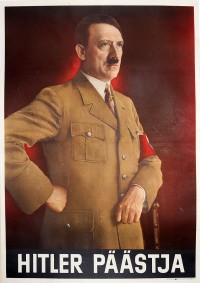

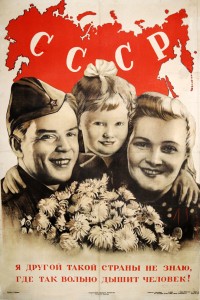

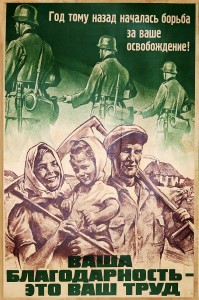

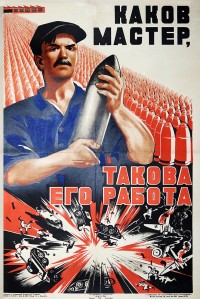

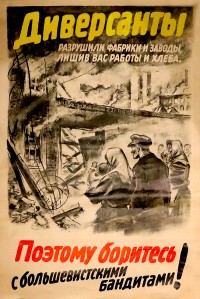

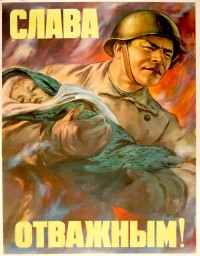

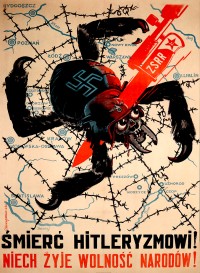

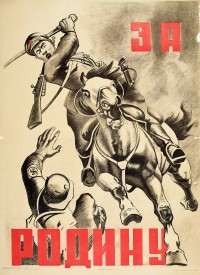

Soviet authorities used radio, films, posters, and other forms of propaganda to make appeals for loyalty tailored to distinct audiences. For communist true believers, the call to party duty sufficed. For an urban population habituated by the cult of Stalin to see the Leader as the source of all successes, Stalin's image and words encouraged heroic efforts. Designed to rally a country reeling from the shock of invasion, he broke his two-week public silence following the German assault by calling on the populace to defend the country despite initial losses and making a dramatic radio broadcast on July 3, 1941, addressing the people as "comrades, citizens, brothers and sisters."

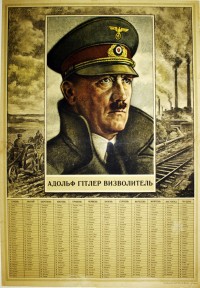

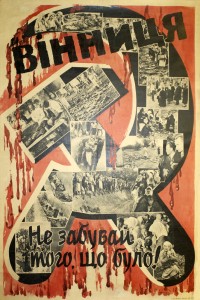

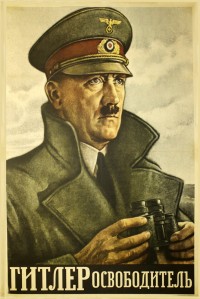

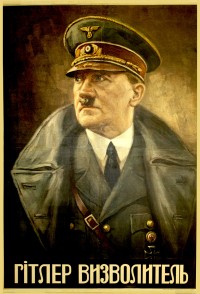

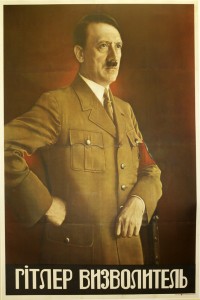

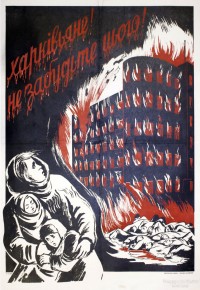

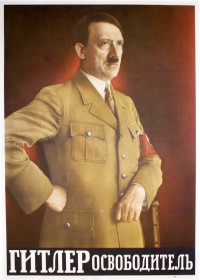

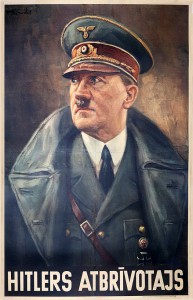

Authorities appealed to peasants to defend the Motherland, thus labeling the fight "The Great Patriotic War." Moreover, this appeal encouraged accommodation between the government and religious authorities. Having been suppressed since 1917, the Russian Orthodox Church returned to prominence with appeals to the large number who continued to believe in spite of official atheism. For others, German actions proved decisive. In non-Russian western borderlands of the Soviet Union, populations initially welcomed the Germans as apparent liberators from the yoke of Stalinism. Many locals however, ultimately turned against the Germans, who alienated potential collaborators by committing atrocities.

During the war's desperate early months, the Communist Party propaganda apparatus sought appropriately heroic examples. A committed young communist, Zoya Kosmodemianskaia volunteered to carry guerrilla warfare behind the German lines, but was captured while attacking troops near Moscow. Defiant on the gallows, she called on her fellow Soviet citizens to fight on in the name of Stalin. Like so many wartime stories, the accuracy Zoya's has been challenged since the 1980s, but such tales once contributed to a powerful myth of unity and unwavering commitment to the cause.

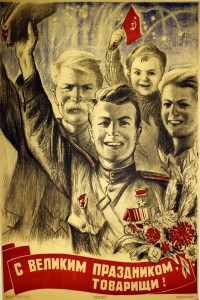

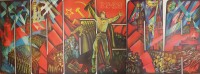

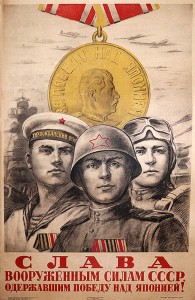

Halted at the gates of Moscow only in December 1942, the Red Army's initial retreat was followed in 1942 by further losses of territory. Finally, in the winter of 1942-1943, the Soviet forces achieved a costly but decisive victory at Stalingrad, which turned the tide of war. By repulsing a significant German counterattack in the summer of 1943, it won a further decisive battle around Kursk and thereafter rolled relentlessly westward. The storming of Berlin proved enormously costly, but it sealed victory on May 9, 1945.

Propaganda placed the laurels on Stalin's head, but public celebrations remained muted at first. May 9 remained a regular working day until after Stalin died in 1953. It was not until after the Khrushchev-era, during the long leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, that Victory Day was given cause for celebrations and slogans. "Nothing is forgotten, no one is forgotten" became the maxim intoned to accompany elaborate official histories, heroic film dramas, military parades, speeches by veterans, and the laying of wreaths at mass graves and war memorials. Initially powerful, these messages were alien to younger generations, who, by the mid-1980s, were two generations removed from wartime tribulations. By the 1990s, the era of glasnost enabled people to challenge myths and question Stalin's strategic blunders and tactical miscalculations. Government archives unsealed in the era of glastnost provided details about the crimes of Stalin only peripherally revealed during the Khrushchev era. The public learned of the pre-war purge of the Red Army's officer corps and of wartime mass deportations of ethno-national groups on trumped up charges of collaboration with the enemy. For some, the perception of the Soviet Union's role in the war changed, while others continued to embrace the traditional narratives.

Surviving those challenges, the traditional cult had rebounded in the 2000s. A managed public memory of victory now sustains the post-Soviet Russian state under Vladimir Putin. Both Russian officials and citizens participate readily in Victory Day celebrations, festooning lapels and other articles with the orange and black striped St. George ribbon. Grand parades of military vehicles and exuberant columns of young, Russian soldiers outfitted in vintage World War II uniforms and arms are the norm. Only popular enthusiasm makes it possible to see automobiles emblazoned with slogans such as a rhyming couplet that translates as "Thanks gramps, for winning the war!"

Suggested Reading and Resources

Lisa Kirschenbaum, The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941--1995: Myths, Memories, and Monuments (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Memories of Veterans of the Great Patriotic War, https://iremember.ru/en/

Catherine Merridale, Ivan's War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945 (Picador, 2006).

Pleshakov, Constantine. Stalin's Folly: The Tragic First Ten Days of World War II on the Eastern Front (Houghton Mifflin, 2005).

Seventeen Moments of Spring, "Battle of Kursk," and "Veterans Return" http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1943-2/battle-of-kursk/http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1947-2/veterans-return/.

Nina Tumarkin, The Living And The Dead: The Rise And Fall Of The Cult Of World War II In Russia (Basic, 1995).

Harrison E. Salisbury, The siege of Leningrad (Secker & Warburg, 1969).

![PP 289: Glory to our Victorious [and] Heroic Army!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-289/pp289-199x300.jpg)

![PP 290: Back to [his] beloved family, back to peaceful labor!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-290/pp290-200x297.jpg)

![PP 483: [Left text] There is only one truth in the world. [Right text] This is as big of a lie as pea soap.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-483/pp483-200x133.jpg)

![PP 528: Drava March 6 – 22, 1945

[Your] national duty has been fulfilled.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-528/pp528-200x291.jpg)

![PP 556: [Text top left panel] Board Of Satire No 1; Department of Propaganda Kiev

[Left Panel]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-556/pp556-200x133.jpg)

![PP 736: What Never Will Happen and What Must Surely Happen

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-736/pp736-200x132.jpg)

![PP 741: In February of 1940 the pilots Sokolov and Kozachenko were flying back to their airfield after an air fight.

It was clear above the snowy clouds. Suddenly Sokolov sighted a group of Belofinn planes in a formation of twelve “Volkers”.

The force of the enemy exceeded ours by six times.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-741/pp741-108x300.jpg)

![PP 844: Take revenge on the German dogs!

“German beasts even reached your home. They stole your belongings. Threw out your wife, Nastia [Anastasia] Galkin, along with the children. As they fled down the street, your wife Nastia was killed by a German bullet. Elder daughter, Olia [Ol’ga], and little son, Vania [Ivan], broke down in tears, Nastia no longer heard them. . .” – From a letter to Private Galkin.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-844/pp-844-catalog-image-199x300.jpg)

![PP 941: Great Patriotic War Poster Newspaper No. 11.

Proletarians of all countries, unite!

Death to the German Fascist invaders!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-941/pp-941-catalog-image-200x133.jpg)

![PP 1056: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1056/pp1056-200x282.jpg)

![PP 1067: Warm dress [clothing] for the Red Army!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1067/pp1067-200x273.jpg)

![PP 1084: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1084/pp1084-200x284.jpg)

![PP 1085: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1085/pp1085-200x280.jpg)

![PP 1148: We wait with [hope] for victory!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1148/pp-1148-catalog-image-200x286.jpg)